Chris Burden

Tate Gallery, London

Art Monthly, Issue 226, May 1999

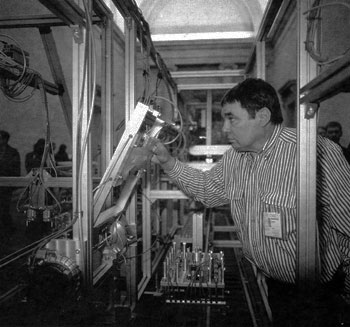

Image: Chris Burden working on When Robots Rule: The Two-Minute Airplane Factory

Imagine the scene: the colossal Duveen Galleries have been emptied of heavy-duty steel I-beam sculptures, bronzes and marbles. The first gallery houses a most extraordinary machine: its 6m long aluminium framework densely populated with an amazing selection of computer-controlled automata, each whirring and running and blowing in precise patterns as they progressively assemble, from its constituent parts, a delicate balsa and tissue model aeroplane. At the end of the machine a fragile cantilevered runway extends 3m into the central Sackler Octagon. The completed aircraft taxies along and launches itself, rubber-band thrumming, spiralling 20m upwards into the cavernous space, eventually gliding back to earth for its maiden landing. This joyful sight is repeated every two minutes as another fresh plane is born and set free, buzzing itself skyward.

As the aircraft land they are gathered up by gallery attendants and sold cheaply to the public, and so they are dispersed around London and beyond. What we're seeing then is not only an entire factory on display, but a whole economic system too. The planes aren't just made before our eyes; they are commodified and sold. So the installation is a microcosm of our industrialised capitalism: a working diagram of the dominant social and economic systems, made comprehensible through transparency and manageable scale. It's an astonishing project, spectacular, entertaining, intelligent, critical and relevant.

You can picture it now, can't you? A wondrous installation, fascinating and uplifting in equal measures; base materials alchemically transformed into elegant flying machines, enchanting the money out of visitors' pockets. It's a magnificent scene. Just don't rush along to the Tate to see it, because you won't find it there. Sure, that's where the installation is based, and crowds gather about it, but the spectacle will remain less than enthralling while the machine itself remains non-functioning. Unfortunately, the only little aeroplane to be found at the Tate is in a glass box, and the artist made that one himself, by hand.

The exhibition was due to open on March 2, and as of mid-April it has yet to produce a single aircraft. What beautiful irony then that Frances Morris should begin her essay with the line: 'Chris Burden has always given museums a difficult time'. Which essay is that? Oh, you won't have seen it because it's in the catalogue which, due to a lack of images, hasn't been printed yet (although by the time you read this it should be available).

Morris is right: Burden does give museums a difficult time. Most of his work, in some way, challenges the institutions that he works with. Often he challenges them politically: what are they willing to do, legally, ethically and self-critically? Here, though, the Tate is challenged practically: it is asked to work in areas alien to its usual practice - it's a sort of institutional assault course, a kind of Krypton Factor for major museums. At this rate, the Tate won't be qualifying for the series final.

This may all seem beside the point; if the machine was working we would be talking about model planes and not inept management. But taken in the context of Burden's practice, it's tempting to think that perhaps he knew the installation would spend most of its time not functioning. The work itself, then, is not so much a machine, but a kind of managerial performance art: we watch the Tate squirm as it tries to deal with software programmers and engineers, all while attempting to remain unruffled before thousands of intrigued visitors.

When Robots Rule: The Two-Minute Airplane Factory is ingenious because, if it fails to work, it simply shifts its focus. If the machine was fully functioning, then it would be worth flying half way round the world to witness, as some people have. But even when it's not working it is still worth a visit; as an artwork it is equally successful, it just has different results.

How can we justify this 'institutional critique' view of the piece? Surely if it doesn't work, then it just doesn't work? Well, ever since his student days Burden has been deeply interested in institutional politics: his first ever performance at the University of California - where he imprisoned himself in a tiny student locker for 5 days - seemed less concerned with performing an act of physical endurance than with the institution's reaction to it (which was to call security, and ask them to bring crowbars). There are numerous other stunning, institution-baiting projects to prove it.

Yes, Burden's work is often about demystifying technological processes, as the Tate's press machine insists, but it is always soaked in politics too. And that is what is so great about this project; while the Tate may have thought it had commissioned a relatively safe project - in so far as it doesn't explicitly undermine its authority - the installation's problematising of managerial structures refuses to be suppressed. It is a gorgeous irony, and one that Burden must enjoy at some level, that this joyful, apparently non-critical installation should have tripped the Tate up so spectacularly.

— End —