Dissolution

Laurent Delaye Gallery, London

Art Monthly, Issue 204, March 1997

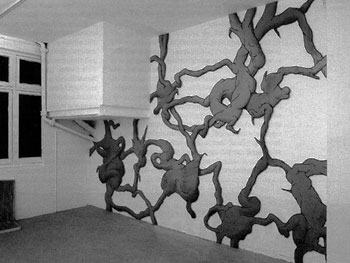

Image: Keith Tyson, AMCHII-CCLXXVIII 'Grey Matter' (installation view, detail)

What can we say? Painting's battle with itself goes on and on, this show being the latest skirmish. The press release astonishingly suggests that work made by young painters in Britain today should not be considered High Modernism but as a blurring of high and low culture. Would that be Postmodernism, then? Hey, hold the front page. But what is really odd, I mean odder than this defence of a 40 year-old truism, is that it coincides with a resurgence of reflexive painting in Britain. Artists like Jason Martin and Zebedee Jones produce work that, if not exactly High Modernism, is at least highly like Modernism. Rum timing on the gallery's part, this.

The show itself is a mixture of hard-core painterly types doing their serious painting thing, and your more pluralistic types doing their try-anything-once-even-painting thing. Yet the one artist who could hold his own in each category, Mark Wallinger, presents, not exactly paintings, but inkjet printouts of computer-generated images. The Scream is an eight-panel cartoon depiction of the crucifixion: the yellow Christ blinks, blood runs down his face in perfect drips, and that's about it. It's like a cheap animatronic 'The Crucifixion Experience'. Clever but dry, it brings a thin smile to the lips.

Gavin Turk's religious theme is his familiar God/Gavin concept. But while Wallinger avoids the inherent issue of painterly skill (having already tackled that one), Turk crashes headlong into it. His GT1 is a misty landscape (at least I think that is mist) with a road, a fence, a small wood and the large letters GT floating in the sky like steely airships. To be generous, we assume that the crummy paintwork is deliberate and hence assume that this is not simply another skilful homage to himself - but a pathetically embarrassing homage to himself, and thus not much of a homage at all. It is like having some Beavis and Butthead weirdoes sending drawings of you through the post because they think that you're, like, totally cool. For Turk, it's the end of a beautiful relationship. But then what does 'dissolution' mean, if not the undoing of bonds, partnership, marriage or alliance?

Relationships feature strongly in the work of Simon Bill, Alain Miller and James Rielly, too. Bill shows My Friend, an oil on pegboard rendering of a mutant Big Bird: three eyes, no legs and an altogether scabrous appearance. The kind of friend no parent wants their child to have. Scrawled on the side of the board is a more sinister title: The Bringer of Happiness. Miller's large, not-quite-blurred painting I Love Eye depicts a heart which boasts the brown eyes of a 70s beauty. The image is as smooth as a mannequin and, although unpleasant, is strangely unaffecting. Reilly's style, meanwhile, has a sub-Tuymanesque simplicity and only when the complexity of the paint transcends this - as in Curious, where its blotchiness suggests that the canvas itself is sweating - does the work gain any real weight.

The most striking work climbs all three floors of the gallery as a kind of cartoon vine. AMCHII-CCLXXVIII 'Grey Matter' by Keith Tyson is a collection of his neural modules (hence the numbering). On the first floor they form a kind of archway, as if the painting brain can only conceive of decorative formalism. The second floor gives us a more all-over scattering, while the top floor brings large anamorphic knots, like Rorschach blots. Is this the moment when painting discovered its own unconscious? Is this a history of art in MDF and grey acrylic? Why do painters make paintings while everyone else makes paintings about painting?

Seemingly at odds with the aims of the show, Angela de la Cruz presents three formalist works. These are essentially monochromes, but their autonomy has been ruptured by a quite severe collision with reality. Sure, Greenbergian autonomy was reduced to absurdity in the 60s by Minimalist objectification, but what is important here is that Cruz does so, not with serially manufactured objects, but with formalist paintings themselves. This she achieves by repeatedly whacking them against the material world - it's as if Greenberg was hit by a truck, and then reversed over again. Her limp canvas reverts from picture plane back to its natural state as woven material. And what does 'dissolution' mean, if not disintegration or decomposition? But this reification of materiality is only interesting in so far as it has been done in a painterly manner - these are neither unprimed monochromes, nor are they Flanaganesque canvas piles. Cruz is a painter, and her work retains its painterly values. Thus her attack on painting is done from within the very ranks of painting itself: her pieces are double-, triple-agents. If we could scrape off the paint to reveal the canvas, what uniform would we find there? Should they be given medals, or shot at dawn? The questions this show wished to pose have been put with more relevance by Cruz. Perhaps it should have been a solo show?

But not so fast, for there is someone else who raises similarly tricky questions about painting. But this person doesn't consider herself to be a painter; I know this because Tracey Emin always says that she can't paint. Which is okay because she has presented, not paintings, but relics from a performance about this activity. Of all the artists' paintings, Emin's are the most naive in their belief in painterly expression. And yet she herself doesn't believe in this, as proved by her emotive, handwritten text that accompanies Under the influence of painting, which ends 'l CAN'T PAINT THAT'. But painting is a useful tool for Emin, for her real strength as an artist lies in communication. All of the objects that she makes function most fully as props, props to her performances - be they readings, talks, or whatever. Emin is inseparable from her work and, like Warhol, she exemplifies the notion of artist-as-artwork. So paradoxically, the artist whose paintings exhibit a traditional belief in painting's function as an expression of the artist's emotions is also the one artist who is the most radically anti-object, and thus anti-painting. This show called for the avant garde, and Emin brings exactly that through her dissolving of art into life. And what does 'dissolution' mean, if not coming to an end, fading away, disappearance or death? In short, life?

— End —