First LEA Gallery Exhibition

LEA Gallery, London

Art Monthly, Issue 212, Dec-Jan 1997-98

Image: Jane Wilson and Louise Wilson, Stasi City (video still)

Cardboard boxes make a pretty good artistic medium. They are cheap, readily available and pack flat. What's more, they also carry a world of connotations ready for careful manipulation. They are the classic urban trash, surpassed only by plastic bags. But cardboard boxes make rather pathetic litter since they lack the immortal morbidity of toxic polyurethane. Cardboard is a mere pimple compared to the epidemic of plastic.

So cardboard boxes have a kind of utilitarian wholesomeness, a throwback to the days when mass-production didn't kill everything; plastic bags come printed with warnings about suffocating babies, but every kid loves to play in a cardboard box. You can even buy chic minimal cardboard boxes for your living room. Some people live in cardboard boxes. We agree, then, that cardboard is a good, warm material of the people - and artists such as Neil Cummings take advantage of these attributes.

Peter Zimmermann's boxes, however, are not like this. There is something less than friendly about Zimmermann's containers, something just that bit too perfect. In short, these boxes are not of the common-or-garden variety that you and I would recognise ... but impostors. For Zimmermann's boxes are corporate boxes, advertising boxes, glamour boxes. You won't find these at the soup kitchen. No, no. Rather, these boxes are fed brie and cranberry bagels as the make-up artist massages their corners into razored perpendiculars while they await the studio photographer. For these are the celebrity cardboard boxes, the boxes that appear in advertisements for their manufacturers. They are, if you will, the Alan Partridge of industrial materials.

It is important that we understand this. These are not boxes of the street but boxes of the studio. Unsullied by use, they are fake utilitarian objects. Functional but for their functionlessness, they are a kind of intellectual litter; boxes, yes, but only in theory.

In his piece Boxes, Zimmermann has screenprinted the vessels - of which there are 60 - with text. Not the text that you would normally find on the protective packaging of a 14" monitor, which these are, but text that you might encounter in a sociological discussion of television (the 'box' supreme). This text is dense, dry stuff - hard to follow. Not least because it is broken up over each container in a manner mimicking the kind of text that you would normally find surrounding a 14" monitor.

Now this text is, I think, broadly critical of televisual culture. And yet it is printed onto the very containers that protect these little monsters as they make their way into our homes. Do I smell a rat? Or even just a mouse? Is this text truly critical? Or is it mere sophistry? Perhaps this is a snipe at the not-quite-critical discussion of popular culture (mantra: popularity equals quality) which rationalises a love of trash. Perhaps the monitors arranged upon the stack, constantly flicking between cable TV channels, are meant as a celebration or as a surreptitious first taste of the drug. Perhaps not. And since the gallery could not receive the broadcasts that the piece required, it has had to make do with previously recorded videos, which doesn't make things any easier for the puzzled viewer. We find that the deeper we probe, the softer the ground gets.

There are other works too: large novajet prints from CD-ROMs. These CDs contain printing information allowing repeated reproduction or, indeed, manipulation of the works. The prints themselves contain images that have been digitally collaged, and again text splinters across the surface. From Rendering (Rendering): 'Render is a program that runs on the PC architecture which allows a user to display graphics objects on the PC monitor with precise temporal and spatial control ... '. The focus is the boxlike, indivisible elements or modular units of an actual or informational architecture. From the same piece: ' ... all this is based on the theoretical distinction between hardware (the material reality of buildings and places) and software (the impact of information and programming on this environment) ... '. Each piece is about the theoretical construction of spaces and the effect of communications upon them. There is even a nod towards hypertext, as the text which runs across the three posters of the work, Temporary Architecture/Presentation of Boxes, skips off the wall and down onto the boxes piled up below.

It is difficult to gauge Zimmermann's position in all this. We understand the area in which he is interested but we cannot pin down his particular angle with any certainty - which is perhaps deliberate. However, there is a degree of specificity about this work which suggests not only that the artist knows exactly what he is doing, but that we should too. Perhaps the intention is to leave the viewer high and dry within a confusing mass of information, but it would be a shame if this promising work set its sights so low. Certainly, Zimmermann is pressing all the right buttons. It would be great if he let us tune in too.

At night you can see the Intergalactic Starlight Observatory from Hoxton Square which, as you might imagine, is kind of trippy. The four large plate-glass windows of the first floor gallery light up, abstract images flaring and swirling hypnotically. The night-trippers queuing for next door's Blue Note club are tranced into the mood. They are a perfect captive audience.

It's all happening in Hoxton Square. Besides the artist's studios and mighty Blue Note, Hoxton Square now boasts the Lux Centre. Housing the Lux Cinema, the London Film Makers' Co-op and London Electronic Arts, the Lux Centre also hosts the LEA's new gallery. The first exhibition, curated by Gregor Muir, doesn't really have a title, nor does it have a particular theme. But this is okay, because there are other artworks around the building which would only have confused matters, had matters been intelligible. These are the three LEA/LFMC joint commissions produced to mark the opening of the centre.

For the last week of October there was the strangest sight: a Victorian conservatory was built in the middle of the square, at an angle so that it seemed to have dropped from the sky. It never looked quite at home in Shoreditch, but at least it perked up at night. This was Conservatory by Housewatch, each of whose six members produced ten-minute multi-screen video works. These were projected onto the windows of the conservatory from the inside, and would run from dusk until 11pm. Small groups gathered around the glowing object and just stood and watched - it was very like a bonfire in the way it held your gaze. The spectacle was ideal for winter nights, but sensibly ended before Guy Fawkes night.

Entering the Centre, we find the other two commissions: Elizabeth Wright's Pizza delivery moped enlarged to 145% of its original size sits massively (boy has it got a big box) in the foyer outside the gallery entrance, guarding the foot of the stairs. The fresh swishness of the new building makes the sculpture doubly incongruous because unlike Wright's enlarged bicycle at the ICA's 'Belladonna' show, whose plausible location and slight physical presence ensured that many visitors failed to notice it, this moped is a massive object. Heavy and unsubtle. Despite the Honda Cub 90's scruffy ubiquity, we never accept this enlarged version as familiar. There is no jocular lightness in its physicality, only the threat of scale, the fear of bulk. The idea is playful, the object brutal.

If you can squeeze past that pizza delivery box you can ascend the stairs and find Darrell Viner's Light Curtain. And it will find you, too. Sensors activate small rows of LED lights as you climb the flights. The stairs, like the rest of the Centre, are thoroughly designed: constructed from metal grating, the entire stairwell is alarmingly see-through. Viner's piece is a permanent installation, and the last of the joint commissions. It occurs to me that if the Centre ever burned down, Light Curtain would look great in the smoke.

We have already seen the first piece in the gallery exhibition, because it wasn't in the gallery but on the windows outside. Graham Wood, with help from Dirk van Dooren, both of the design group Tomato, produced the aforementioned Intergalactic Starlight Observatory.

Inside the gallery, one end is occupied by a video viewing system. Angela Bulloch has made plywood and red-cushioned benches her own and here she has produced four of these, each with a bottom-sensitive seat. Four televisions are also present, playing continually. Sit in front of a monitor and its soundtrack will be switched on. The excellent videos, from the LEA's extensive collection, have been selected by Bulloch. Klaus Maeck's Einsturzende Neubauten Liebeslieder documentary, detailing the demolition job that is the music and performances of Einsturzende Neubauten (famous for using jackhammers to drill through the stage at the ICA, attempting to reach the tunnels rumoured to exist below). Sadie Benning's thoroughly disarming German Song. The Duvet Brothers' classic scratch video Blue Monday. John Cage's Interview/Performance in which Cage is interviewed by Richard Kostelanetz who, we are told, is suffering from laryngitis. He speaks in a theatrical whisper.

The viewing system is really good if you are alone, or with a friend. If you are already viewing a monitor when another visitor arrives, however, they tend to be too intimidated to view another video, turning the sound on as it does. If this is a problem, then it is not the only one. The entire exhibition is problematic. The difficulties of asking an artist to make a work in order to show off your video collection is one thing, asking an artist to make a work in order to show off your new staircase is another, asking an artist to make a work in order to show off your new windows another still, while asking a group of artists to make a Victorian folly for a week while local galleries struggle to cope with the area's new-found exclusivity is yet another. You can see why the Lux Centre failed to impress every local resident. However, none of this amounts to a hill of beans when you see Jane Wilson and Louise Wilson's new work.

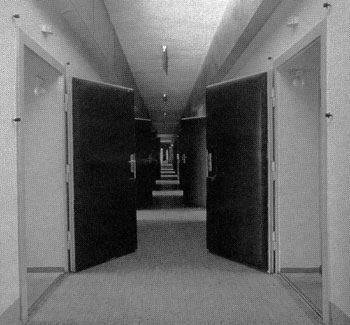

Push through black rubber curtains into a blackened room. About six metres square. Four video projectors create two double-corner projections, diagonally opposite each other. Filmed in East Berlin, the camera roams the former headquarters of the GDR's intelligence service. Deserted, obviously. We move through vacant rooms, through padded double-doors and abandoned medical quarters. Each projection frequently mirrors its corner-partner, sometimes with short delays, sometimes with a complementary, reversed action. We flick between the twinned images, then check the other images behind us. Trying to work out links between scenes. Begin to recognise scenes. Learn the loop. Follow the narrative.

Lights flicker on with a deep hum. This was the office of the last director of Staatsicherheit. A lady picks up her handbag to the sound of a camera shutter. We don't see her face. We never see anyone's face. We move through offices, past old-style telephones and television sets. Past typewriters and chairs and door after door after door. It is airless. A female figure passes in a paternoster going up, going down on the other screen. We see her skirt and her shoes. This is a horror film. A horror film in which the horror has passed, but the suspense remains.

Then it happens. Just as we were settling-in to this trawl through the building with the dark history, it happens. A figure floats past. A female figure in an old-fashioned tracksuit with bare feet. Gliding slowly through the room. Not touching anything. A chair lifts up. A flask floats upwards. The airlessness has become weightlessness. The unreality of the building has become manifest. An abandoned spacecraft, it belongs to another world. But a world within our world. A world whose telescopes are trained on us. This is Stasi City, Jane Wilson and Louise Wilson's strongest work to date.

— End —