Computer World

The Tannery, London

Art+Text, Issue 57, May-Jul 1997

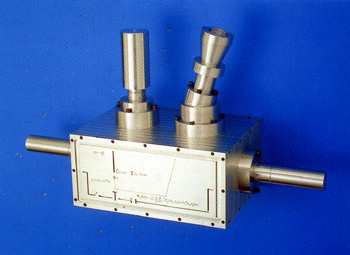

Image: Mark Firth, Box of Random Events

Round the back of the 'London Dungeon' tourist trap, through a long, dripping brick tunnel under a railway, The Tannery can be found. It feels like the wrong decade; this could be the 1940s, even the 1840s. Entering the old brick warehouse does nothing to relieve this time-travel sensation. Apparently, 'Computer World' is an ironic title, as there is not one computer in the show. But the title still jars since the show seems to have been transported from some legendary, pre-ironic era. The exhibits' retro-styling seems oddly authentic, not cannibalized. And yet isn't this London, style capital of the nineties?

Inside, Tim Olden's exhibit could be mistaken for ceiling supports, but his metal poles are actually 'theremins': a B-movie whine changes pitch as one moves closer, translating proximity into sound. One is drawn to touch them, but fingers soon grow numb from the cold. For all its mundane appearance, this is pure Star Trek. Reinforcing such trekkieness are two works from Dante Leonelli's 'Neodome' series of the 1970s: large wall-mounted plastic domes glowing with neon lights, whose colors slowly pulse like some nebulous higher intelligence.

Upstairs in this long narrow building are Annabel Howland's viral splatterings. Resembling magnified bacteria, they are actually bank note patterns - though if you enlarge bank notes you'll find that they are in fact riddled with germs. Perhaps obscure diseases to infect only rich tourists? Far more cleansing is Mark Firth's Box of Random Events, clicking away to itself, as if popcorn sounds were emitting from its amplifying tube. It's pleasant and calming, or at least would be if it weren't for the fact that this is a Geiger counter measuring the decay of the sculpture's radioactive core.

Running around the gallery's next floor is a 200-foot tube filled with water, Tim Meacham's Mae West. Inside the tubing is a little piastic pilot with a map on his knees, carried helplessly along in the flow. Nearby, there's Attilo Csorgo's tilted bolt, whizzing around and describing the outline of a glass in the way that helicopter blades form discs; and Mathieu Mercier's three large houseplants, each of which has supporting trellises for its leaves. In another room is Christopher Pauling's 'beast.' This three-meter cube consists of 27 individually inflating clear plastic units: floor pads trigger various combinations into life, making the work wheeze up and down, like some stranded alien jellyfish gasping its last.

Just sitting there finally, extraordinary and purposeless, is Stephen Hughes's Gate Crasher, a luminous resin cast of a meteorite from the British Museum. As in Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark, the object appears to be boxed up and stored in yet another secret government depot. This goes for the show as a whole. Both wonderful and sad, it is a retro-X-Files - reeking of nostalgia for the future. But in this world of collapsing space and delimited borders, it seems that the days of mysterious objects are over, leaving only hard utilities and facts. The real irony is that computers are now too numerous to be numinous.

— End —