Sensation

The Royal Academy, London

Art+Text, Issue 60, Feb-Apr 1998

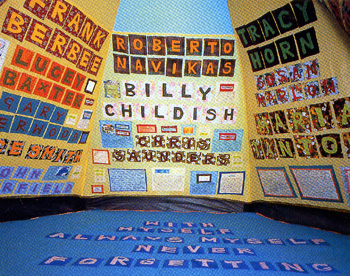

Image: Tracey Emin, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995

Sensationalism is a curious thing; merely to comment upon it is to accelerate its velocity. The same could be said for 'Sensation,' at London's Royal Academy of Art. Start with the art works: the fact that they were selected from Charles Saatchi's private collection; that the Royal Academy - against many of its members' wishes - initiated the show; that it has been on the cover of most national newspapers in the weeks both preceding and following the opening. Or, concentrate on the works themselves, but as there are 110 of them, this may be impractical. So it goes with sensationalism; it evades substance all too neatly.

We've seen most of the work before: Jake and Dinos Chapman's Zygotic Acceleration... (1995); Tracy Emin's appliqued tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 (1995); Damien Hirst's fly piece, A Thousand Years (1990); Gary Hume's Vicious (1994); Sarah Lucas's Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1992); Simon Patterson's tube map, The Great Bear (1992); Mark Wallinger's recent video Angel (1997). However, we already knew how good these pieces were (although it's nice to be reminded), and there are few relatively unknown artists in the show. Of these, Ron Mueck is the only one to really astonish us, with what may well prove to be his seminal work, Dead Dad (1996-7) - a serene, half-size sculpture of the artist's father's naked corpse. It's so convincing that I overheard some visitors inquiring, bizarrely, whether or not it was real.

Most of the work in the show looked perfectly at home in the RA's traditional, but over-the-top galleries. Indeed, the RA's absurd architectural features, when seen in this context, begin to look like installations themselves, which is to say the space doesn't overpower the art, but vice versa. This is significant only because it wasn't so very long ago that Saatchi's huge, minimal warehouse of a gallery was being praised as the only way to show contemporary art. Such austerity certainly suits works like Rachel Whiteread's Ghost (1990), which is poorly served here, but seems excessive in relation to work which circles around everyday experience.

Much of the content in 'Sensation' is robust enough to hold its own in cluttered environments, which is to say it has been obliged to function like advertising. Indeed, the British press has often made the claim that these works, in their striving for maximum impact and immediacy, are little more than adverts for themselves. But it is a mistake to write them off on this count. Case in point: instead of featuring a piece from the show on the poster, the RA farmed out the job to a commercial agency. The result - an image of an outstretched tongue touching the tip of an iron - has immediate visual impact, but is utterly boring. In fact, commercial images rely on unproblematized cliches of collective consciousness, whereas nearly everything on view here has a conceptual component that mitigates against simplistic readings.

Even so, the notion of 'visual immediacy' remains the only attribute that comes close to unifying the works. Furthermore, it seems as if the organizers were assiduously courting dumbness. Saatchi's hanging (he played a major part in the selection and installation) often groups works together in the most inane way imaginable (this is the animal room, this is the domestic room, etc.), resulting in dreadful juxtapositions that emphasize only the most literal meanings (this, it seems, betrays an adman's 'understanding' of his own art works). That having been said, there are some inspired touches which could not have worked anywhere but the Royal Academy: for example, Sam Taylor-Wood's 1995 Killing Time video installation, which is exquisitely framed by four ornate plaster frames decorating the walls.

That this is an idiosyncratic survey show should come as no surprise as academies have only ever written partial histories. In any case, the show's only real intention was to be a success, which seems to mean bums-on-seats. The RA has got its crowds all right, as members of the public who have never seen such things gorge themselves on the sickly-sweet visual overload. However, the fact that 'Sensation' may cost the RA's Exhibitions Secretary, Norman Rosenthal, his job, may yet be considered by some Royal Academicians as its greatest success.

— End —