Notes on a Heart: Soho and Three Short Films

Exhibition Catalogue Essay

Jordan Baseman: Dark is the Night, The Photographers’ Gallery, London, April 2009

The Subject in Soho

I live in Soho. Writers prefer not to speak in the first person, but Soho makes a subject of us all. It is a place where you are confronted and forced to respond on a regular basis. You may simply be bumping into your neighbours just like in any other village (and Soho is a village, although its four thousand inhabitants are always outnumbered by visitors – it is a place to be shared, not owned). Or you may be confronted by market traders shouting out to you, or flyer distributors, or marketeers, or chuggers, or pedicab riders, all offering you something. It is the same at night, but with a different crowd: corner pushers and pimps, street clippers and clip-joint girls, the homeless and the junkies.

You cannot drift above this as an impassive viewer. You must speak when spoken to, decide how to react and interact. Jordan Baseman, when filming here, was frequently confronted and asked to play back scenes he had just shot even though his 16mm film camera could not give up its footage like a digital camcorder. The filmmaker, like everyone else, was part of the street life rather than a voyeuristic passerby; in Soho we are forced to be an individual subject, dragged into the action as an active participant. So, yes, I live in Soho. Berwick Street, specifically.

One Street in Soho

Berwick Street runs from Europe’s über high street, Oxford Street, down to a junction with Peter Street and the choke point of Walker’s Court: the seediest crossroads in the West End. This southern section of Berwick Street is a useful indicator of Soho’s varied charm.

The short stretch from Broadwick Street south is – among other things – home to: the bedraggled remnants of a once-vibrant street market; highly specialized record shops (the vinyl variety); an audio post-production firm; an independent household goods shop; long- established fabric shops; a betting shop (and its attendant drug dealers who nest like cuckoos in the premises); a small supermarket (described by a friend from Hackney as the scuzziest in London); a vintage clothing store; what used to be called a ‘head shop’, selling bongs and seeds (which are sold ‘for worshipping only’ with a disclaimer: ‘it is illegal in Britain and many parts of the world for them to come into contact with earth, air, water and light at the same time, under no circumstances are they sold for that purpose’) and which also doubles as a fancy dress costumers; a hairdressers; a 17-storey block of flats; an Islamic faith centre (where on particular holy days crowds spill out into the market, laying prayer blankets among the discarded cabbage leaves and cherries, and praying towards Mecca); a pair of pubs; a Christian fair trade shop; a walk-up brothel; a whole food café; a French bistro; a chip shop; a celebrity-filled French patisserie/Japanese tea house/Chinese dim sum restaurant; and what appears to be a disused travel agents but which in fact houses the food preparation area for the aforementioned Michelin-starred Chinese restaurant. Numbers one to five Berwick Street are currently undergoing redevelopment and this has displaced – but only the short distance to Peter Street – a host of brothels and sex shops, including the rather specialized establishment that is Spankarama.

This eclectic mix, far from unique in Soho, emphasizes that at the heart of the area is a turbulent blend of barely reconcilable impulses: creative, community minded, spiritual, hedonistic, illicit, high-end, low-end and every end in between. Soho is a place to find whatever you want, and a few other things besides.

Capillaries not Arteries

Other than its two grand squares, Soho has always been a jumbled mass of alleys and small courtyards. This is partly a relic of the ancient field boundaries that divided it prior to its first developments in the mid 1600s, but it is also due to the slump into poverty that ensured few grand thoroughfares were built. Although Soho is less than one square mile in size, it still retains over seven miles of streets and alleys, and these tiny capillaries ensure that civil society clots in Soho.

Although Soho was initially developed as part of the move west towards the City of Westminster in the 1650s, the City of London’s Great Plague of 1665 and Great Fire of 1666 created a pressing need for homes and ensured that any grand schemes for Soho were soon outpaced by hasty construction work. The nobility that built their manor houses around Soho Square in the 1650s – around 80 titled residents lived in Soho – soon moved on when the masses arrived; within a century all the nobility had gone, a century later and the area had become slums. By the 1850s the Berwick Street sub district of the St James’s parish was one of the most highly populated in the whole of London, with a population density of 432 persons per acre, or one person per 100sqft of land.

At the time, while Karl Marx lived round the corner in Dean Street working on Das Kapital, Peter Street’s dense housing was described as ‘a disgrace to humanity’, and nearby Duck Lane a ‘hot-bed of disease’ and ‘nursery of crime’. The little courtyards and alleyways were despised by civil planners, and several new slum-clearing routes were opened up with a clearly stated intention: ‘cut the cancer right through the middle’. The alleyways, courtyards and cul-de-sacs choked the urban body, and the Metropolitan Board of Works intended to drive clean new arteries through them (it was an idea that would return in the 20th Century). But although times may change, the previous uses of an area generate its idiosyncratic street patterns, and a unique character evolves from its storied history. Experience is formative of personality.

Nasty Piece of Stuff

Image: Jordan Baseman Nasty Piece of Stuff

The first of Baseman’s films is the most striking: a powerful tale relayed with engaging honesty. While the dramatic drive of the narrative is gripping, it is the protagonist’s tragic naivety and heroic restraint that is compelling. It is a cautionary tale for a time – not so long ago – when homosexual acts were utterly proscribed by law. While the story itself is not set in Soho, the narrator, Alan Wakeman, is a well-known Soho resident and active member of the local community. The area named after its hunting past has for some become a refuge.

Baseman links the dramatic urgency of the narrative with accelerated shots of Soho’s electric nights, each pause for breath matched to a sudden blackout of the visuals – the imagery cutting away from the frenetic street scenes and plunging into a black void of self-doubt and solitude. The staccato rhythm lends a fit-inducing visual stress to a tale filled with dark adrenalin, hopelessness and, ultimately, a magnificent dignity.

The narrative arc runs from self-loathing, victimhood, acceptance, and concludes with a sense of forgiveness – not for the villain, but self-forgiveness. Wakeman ultimately rises above the base cruelty of the night predator that he encountered, and the film builds up to a calmness rather than a crescendo. The events described are being revisited long after they happened, and this gives a sense of hope; the victim has not been identified by that role, and instead moved on to forge a life of his own making. It is ultimately a tale not of suffering, but of empowerment.

Tolerating the East End in the West End

A whole slice of Soho’s peculiarities can be understood by thinking of it as a piece of the East End within the West End. Many of the characteristics that defined East London can also be found on a smaller scale in Soho, chief among these being a poverty in the 1700s that enabled immigrants who fled their homelands to populate the areas, setting up their own churches, workshops and stores. The Huguenot churches and cloth workshops of Spitalfields are mirrored in Soho, as are the Greek churches, the Italian delicatessens, the Algerian coffee shops, the Jewish markets and, more recently, the Chinese quarters and Islamic centres. While Soho’s small size and occasional pockets of prosperity have prevented it from struggling with the corrosive, all-consuming poverty that blighted the East End, the multi-ethnic populace and artisanal history is still apparent. Soho, however, also has additional ingredients brought in by the area’s proximity to extreme wealth, as well as its long history as a place of fine dining, entertainment and all manner of revelry.

Perhaps only one characteristic can encompass this eclecticism: tolerance. And this is something that – despite myriad minor frictions – Soho excels in. One recent sociological experiment, for example, involved two men walking through central London holding hands, with a researcher following to note if passers-by turned to look. The result was that the pair drew stares wherever they went, but as soon as they crossed into Soho the glances stopped – tolerance can be measured by the width of a road.

This defining tolerance has ensured that Soho’s diversity has been retained – even encouraged – and has sustained it as a place of vibrant contradictions: the very antithesis of the ordered and zoned monocultures that the planners dreamed of. Soho’s inclusivity allowed the sex industry to operate, and it had a foothold here long before its well-documented boom during the years of gangster control and police corruption in the 1960s; it should not be forgotten that Casanova was prowling Soho way back in the 1700s.

Dark is the Night

Image: Jordan Baseman Dark is the Night

Baseman’s second film has a metaphorical title. The night is not actually dark in Soho; it glows with electrically excited elements. Neon, mercury, argon, sodium, xenon, sulphur, gallium arsenide. At the approximate geographical centre of Soho, at the heart of the capital’s heart, lies the district’s most photographed scene, Walker’s Court – an alleyway dominated by the sex industry. Yet this alley is the most brightly illuminated street in the area, filled with neon signs and arc lights. This luminescence draws visitors, and where there are visitors so there are predators. So the street is, after all, like the night: dark.

Baseman uses a stop-motion technique to film the late-night-early- morning streets, giving the footage an old-fashioned feel, like that of a hand-cranked camera or flipbook viewer. There is a magical quality to his bleak imagery, a wondrous sense of half-movement that reminds us of the effect that so captivated early cinema audiences: life breathed into frozen moments.

There are very few figures in these deserted scenes – the result of months of selective filming and editing – as if people move too fast for this pensive technology (Soho does not empty at night; more pedestrians pass Peter Street in the small hours of the morning than the afternoon). We see doorways, neon lights, unfolded cardboard boxes for street sleeping. Wet pavements blush through a range of reflected colours under the Piccadilly lights, the alchemical glamour of the night turning the base into the beautiful.

Lucy Browne embodies – in an overt and literal fashion – the contradictions of Soho life. Since Soho is London’s playground, where the capital unleashes its desires and fantasies, so by extension Browne reveals the strong currents of complexity that flow through the broader populace beyond Soho’s inhabitants. These irrational desires run under the day-to-day surface that the city usually displays; a seam of flammable oil within the stratified bedrock of the human psyche – the most potent energy is always the most deeply buried.

Browne’s meandering monologue reveals snapshots of a fractured life story that, like a cult B-movie script, sees an unfullling workaday existence traded for the exotic life of a sought-after transsexual prostitute and drag queen hostess, with multiple wives and children dotting that trajectory like anomalous results in an experiment. In among the discussions of other people’s sexual fantasies and surging desires, which are dealt with matter-of-factly like the true professional that Browne is, are hints at the narrator’s own peculiar quirks and irrationalities. For example, her rule against servicing French men because of their perceived lack of gratitude for the British and American servicemen who lost their lives liberating France during World War II, and because of the fact that French farmers often go on strike. It’s a moment of prosaic silliness, an absurd foible indulged, and it sends a gush of giggles bubbling forth from Browne. She knows this logic doesn’t work when stated out loud, held up for inspection in the light of day. This is the revealing nugget, the Freudian slip that fractures Browne’s facade, bringing the professional who deals in the irrational to a point of her own irrationality, and so we are reminded again of the nether world of the psyche (rather than the nether regions of the body) that Browne’s trade actually relies upon.

Grey Area

The illicit, semi-legal and transgressive all find a home in Soho. The most visible manifestations of this are the brothels, the sex shops and clip joints. But even minor transgressions, those that operate in the grey area of legal loopholes, seem to be drawn to Soho. Whether it is guerrilla advertising written on pavements (a patch of path cleaned via a stencil so that a logo can be discerned) or the semi-legal pedicabs that swarm the streets at night, there is always a loophole to be exploited, an angle to be played, a rule to be bent, twisted and plucked off into an oxbow.

Howard Jacobson, a Soho resident, once wrote about the fact that here even the most mundane of activities can take on an illicit character: “On hundreds of markets throughout the country you are encouraged to believe that what you’re buying – the roll of lino, the Limoges china tea-set – has fallen off the back of a lorry; only in Soho do you get the feeling the tomatoes have.” It is true; somehow buying a scoop of fruit on a Soho street can feel like a shady activity, one where you might, as Jacobson continues, “ask for bananas sotto voce, in the hope the police aren’t watching.” But this is only in keeping with long traditions; Berwick Street Market itself began in 1778 as an illegal extension of local shopkeepers’ retail space, and remained in breach of regulations for over a hundred years until it was finally recognized as an official street market in 1892.

The Planner’s Will to Order

The area’s unruliness draws the authorities’ gaze in cycles – one decade officials look the other way, another and the bureaucrats’ attention burns holes in it – and many of Soho’s problems through the centuries have sprung not from gangsters, drug dealers or n’er do wells, but from the decisions of the authorities.

Soho was under attack again through the 1950s, 60s and 70s; planners wished upon it a futuristic fantasy that would see the old district demolished and replaced by a series of helipad-topped 30-storey high-rises connected by walkways in the sky and an urban motorway charging through Piccadilly Circus at ground level. Soho has always been the kind of place where grand schemes are driven through, clearing that which the authorities deem unwholesome: three of Soho’s great thoroughfare-boundaries, Regent Street, Shaftsbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road, were all smashed through existing developments.

To demonstrate the viability of the modernist fantasy, work began in 1959 on a half-scale tower (Kemp House on Berwick Street, completed in 1962) before an outcry from residents, and the subsequent founding of the Soho Society, forced the cancellation of the master plan. Working on the designs for Kemp House was a junior architect, Alan Wakeman: the subject of Baseman’s first film and an active member of the Soho Society. It is fitting that the Kemp House tower itself, this prototype for an abandoned futurist city, would become home to one of the bohemian figures that so defined Soho in the latter part of the 20th Century, the legendary drinker and occasional writer Jeffrey Bernard.

The Dandy Doctrine (A Delightful Illusion)

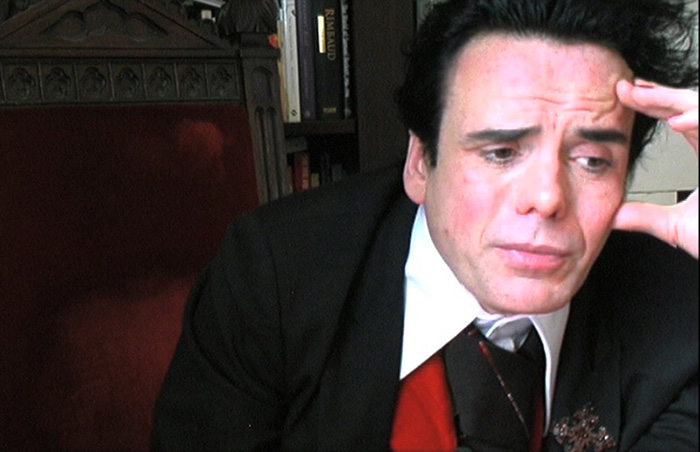

Image: Jordan Baseman The Dandy Doctrine (A Delightful Illusion)

It is the eyes that give it away. Sebastian Horsley is the only narrator we see in Baseman’s three films because he is the only one we need to see. The revelatory openness of Wakeman and the frank, defiantly unguarded comments of Browne reassure us that we are not being led up the garden path. Horsley, however, is a self-confessed dandy, a knowing construct, and Baseman gives him the rope he needs.

Despite theatrical pleas to be shown in a good light, Baseman shows Horsley the mercy that we know he craves: precisely none, like a Warhol Screen Test. And for all his plays at archness, aloofness and camp claims to grandiose failure, it is the grasping hesitancy and sense of doom that we read in his eyes that are the convincing signs that he is a genuine character. He works so hard in his performance, but it is only when the show crumbles that we actually believe him, or rather believe in him.

That most famous of Soho’s dandies, Oscar Wilde (a local restaurant features a Wildean witticism on its menu, not because of literary pretensions but because he said it while eating there), is the model for Horsley’s love of aphorisms and loudly stated philosophies, but unlike Wilde Horsley need not declare his genius. Baseman shows this by editing Horsley’s quips together to reveal their pre-scripted, rote origins – a fact that Horsley readily makes defeatist gags about. Horsley’s attempts at his own Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young may be witty and illuminating, but they are out of place – or, rather, out of time. Wilde’s published list of quips had serious bite because it turned upside down the Victorian values of the day, and yet it used, to spectacular effect, literary art – the height of cultural expression. As the academic Jonathan Dollimore put it, Wilde’s greatest transgression was to be an outlaw who turned up as an in-law, and thus Victorian society could neither laugh him off nor ignore him. A century later and Postmodernism would repeat Wilde’s trick of gaining power through an inversion of values, but this time by celebrating a confused, contradictory dumbness: its heraldic list of one-liners would be Jenny Holzer’s Truisms.

Now, years after Postmodernism’s hyper playfulness has been deadened by the booming sound of two towers hitting the ground, the ‘nothing really matters’ argument feels like a front, and that goes for Horsley as well as Holzer (whose recent work is overtly political and purposeful). Not only has the shock of Wilde’s inversions been diluted by Postmodernism, so this brand of theatrical dandyism seems disconnected; an indulgence at a time when the West has had a stomachful of its own indulgences. Luckily for Horsley, he can’t really pull it off anyway, and the rather tragic sense of emptiness that Baseman captures (in contrast to the stylised and showy photographs of Horsley that the camera spots around his home) ensures that he is revealed as a convincing character of our time: someone searching for a sense of purpose or completeness and finding that the pleasures of western excess are simply not up to it. Having done it all and found that it is still not enough, he is evidently still reaching out – still searching – and the hollowness he claims to champion clearly does not bring a sense of liberation to the soul. You can see it in the eyes.

A Queen’s Rules

On Ramillies Place, sharing a street with the Photographers’ Gallery, there stands an old cell preserved within the Court House Hotel, formerly the Marlborough Street Court House. It was in this cell that the Marquess of Queensbury – an upper-class thug whose name is remembered for codifying boxing – was held when Wilde fatefully called him to account for slandering him as a sodomite. Infamously, the case swung full circle and it was Wilde who was found guilty and eventually sentenced at the Old Bailey to two year’s hard labour in Reading Gaol – effectively a death sentence at the time. While Soho couldn’t save Wilde, despite briefly taking his oppressor’s freedom, we learn from these events that Wilde refused to turn a blind eye to Queensbury’s abuse; he even refused to flee the country when it became apparent that he would be arrested and tried for gross indecency. For all his dandyish insistence on the primacy of aesthetics and his revelling in notoriety, Wilde would not allow a thug to cow him because here was a question of social justice that mattered.

Baseman’s films reveal what matters. They often rely on a sense of conflict, either internal or external, and through this allow us to empathise with each character, however exaggerated or extreme their personalities may seem. Yet for all that empathy, they also remind us of differences, and these films show us that differences don’t have to be a secret in Soho – quite the reverse, they are to be celebrated. Baseman’s three films – this oral history of sex – is emblematic of the bitter cruelties, tender perversions and vulnerable humanity of a wider group of folk, beyond these three subjects, beyond Soho, beyond London.

— End —